Julie Graves Krishnaswami

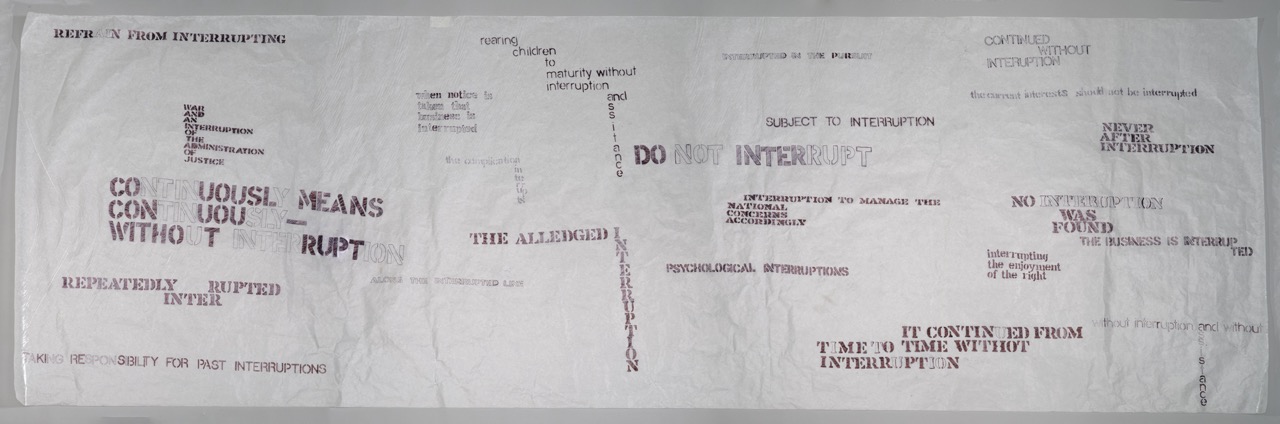

Do You Have An Opinion on the Series of Interruptions?

vintage stencils and ballpoint pen on glassine paper

35.5 × 120 in.

2025

An Interruption causes a shift in attention. Whether it's a phone call, an email notification, a colleague asking a question, a child with a need, or even an internal thought, a shift in attention requires our brain to disengage from what it was doing and reorient. Mistakes are made, and focus becomes fragmented. Dealing with an interruption adds to our cognitive load. This is mentally demanding. Frequent interruptions can lead to feelings of overwhelm, stress, and frustration, contributing to burnout and decreased well-being.

Interruptions take the form of thoughts, worries, or the urge to check social media. The ability to manage interruptions and maintain focus is related to our attentional control. This involves the ability to block out distractions and interruptions, keeping the goals and progress of the primary task active in working memory even when an interruption occurs, efficiently shifting attention to the interruption when necessary and then back to the primary task.

Yet, an interruption is also a pause that creates space, can be loud or quiet. It can be world-changing and revolutionary, even a “happy accident.” An interruption can force the mind to shift, potentially leading to new perspectives or connections. It can break you out of a "rut." Interruptions can be a source of new information or ideas that you weren't actively seeking, leading to unexpected learning or opportunities. Brief interruptions can serve as a break, providing a mental and emotional respite. For routine or monotonous work, interruptions can provide a welcome change of pace, break the boredom, and make the work more stimulating.

This work presents phrases about interruptions excerpted from court opinions collected at random over time. The phrases are stenciled on a long sheet of nearly translucent, glassine paper. Decisions, also known as judgments, orders, or opinions, are the work of the judiciary, are fundamental to the legal system, as they resolve disputes, interpret laws, and, especially in common law systems, like the United States federal and state systems, establish precedent that guides future cases through the principle of stare decisis (let the decision stand).

Artist Statement

Office work; School work; Home work.

Bodies are shaped, contorted, and deformed by labor. My work focuses on the conditions of labor in everyday life and how those conditions impact the body. By interrogating my experiences as a woman, mother, lawyer, academic librarian, and medical patient with a chronic illness, I aim to unpack norms around work and how labor structures physical time, expectations, habits, and routines. On the surface, it may appear that I am the subject of my work, but my work is not about me per se. Instead, I use my body as a stand-in for the body of everyone who labors. In doing so, my goal is both to present this image to others for contemplation and to occupy my body’s intimate experience of the conditions of labor from a slightly distanced perspective. Addressing anyone who works—domestic or outside of the home, in whatever form—I aim to translate the affective experiences of work into consciousness.

Constrained and motivated by educational credentials and the collection of career “gold stars,” I’ve spent my whole life working towards or shirking forms of work. The residue of this search and the absurdity of the white- and pink-collar spaces that I am privileged to inhabit have left their trace on my body and my psyche. Drawing on the conditions in contemporary workspaces, including the classroom, academy, household, and medical office, among others, I spotlight collective pressures and sites of peril foreshadowing possibilities for protest, resistance, and humanity. Awareness surrounding the robotic assumptions and behaviors about one’s working conditions sparks contemplation, inquiry, and perhaps imagination.

I produce artist books, interventions, performances, works on paper, and textile/fiber-based materials. Drawing from social and legal history as well as critical theory, taking my inspiration from conceptual and feminist art practices, I use interdisciplinary research methods to frame my analysis. But I come to my work from the practice of law. The forms and dialects of my legal training organize my artistic practice resulting in subtly humorous but structural observations about contemporary conditions of labor.

Artist Bio

Julie Graves Krishnaswami (b. 1976) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work interrogates the intersections of labor, law, gender, and chronic illness through a feminist lens. She creates artist books, performances, interventions, videos, and installations, repurposing legal documents and texts.

Through her practice, Krishnaswami explores the embodied experiences of work, conditions of labor in everyday life, and how those conditions impact the body. She invites viewers to consider the nuanced experiences of labor and the personal narratives within professional contexts. Her art is a conduit for exploring how power structures and societal expectations shape individual and collective experiences.

Krishnaswami’s work has been exhibited and performed at the Joanne Toor Cummings Gallery, Connecticut College (New London CT), Artspace (New Haven, CT), the Yale Divinity School (New Haven, CT), the Lyman Allyn Art Museum (New London, CT), the Annette Howell Turner Center for the Arts (Valdosta, GA), among others. Krishnaswami was the recipient of the prestigious Puffin Foundation Grant in 2023.

Krishnaswami holds a BA from Reed College, a JD from the City University of New York School of Law, an MLIS from Pratt Institute, and an MFA in Visual Art from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is the Associate Law Librarian for Research Instruction and a Lecturer in Legal Research at the Lillian Goldman Law Library at Yale Law School.